From Sacred to Secular: Stained Glass at MAD

To mark the closing of Brian Clarke: The Art of Light, a retrospective look at how MAD has changed perceptions of stained glass.

In the second-floor stairwell at MAD, Judith Schaechter’s Seeing is Believing can be found soaking in and reflecting the sunlight from the street outside. Scheacter’s vibrant, illuminated jewel-like composition of kaleidoscopic imagery swirls across the four panels of stained glass—made all the more exhilarating by the feeling of precarity from peering over the ledge of the large floor to ceiling windows onto the street. Permanently installed since the building opened in 2008, Seeing is Believing is just one example of how MAD has challenged our expectations of stained glass over the last fifty years. From the abstracted church windows shown in the galleries in the 1950s to the transilluminating stained-glass screens shown in the exhibition Brian Clarke: The Art of Light, MAD has advanced stained glass as a modern and contemporary art form that pushes the boundaries of material and tradition.

Religious Art, Architectural Stained Glass, and the Role of Robert Sowers

While the ecclesiastical history of stained glass is well known and visible in popular culture and media, less so are the craft’s innovations in the twentieth century. Following World War II, there was a proliferation of new work in stained glass. In Germany, where much medieval stained glass had been damaged or destroyed by bombing, churches began the work of repair. German artists like Georg Meisterman, among others, presented a strong architectural engagement with stained glass during this period. Innovating in their abstracted compositions and use of lead, often their stained-glass works were evocative of the death and mourning pervading post-war German society. These artists helped to establish West Germany as a hub for stained-glass education that attracted numerous artists from around the world. One such artist, Robert Sowers, studied stained glass in the United Kingdom and traveled to see this new style of glass in Germany. His subsequent artistic work and published writings supported the emergence of stained glass as an architectural art form in the United States, as did his involvement with MAD, at that time called the Museum of Contemporary Crafts, which would last decades.

Sowers first exhibited at MAD as a part of the 1957 exhibition The Patron Church, focused on contemporary artists and also marked the first time that stained glass was shown in MAD’s galleries. Although the stained glass shown was specifically for sacred spaces, the exhibition pointed to the growing interest in stained glass as appropriate for secular exploration of material and subject matter. An installation photograph of The Patron Church shows a narrow stained glass work by Sowers, titled Rebirth (pictured). Made for the Stephens College Chapel in Columbia, Missouri, the window is fragmented by the crossing leaded lines containing glass in a range of pale yellows, recalling medieval compositions. Sloping, narrow lines of red and blue lead to a dark, almost opaque form, suggesting the bud of a flower. Works such as Sowers’ revived the traditional aesthetic of stained glass using abstracted, geometric forms.

Sowers’ work was shown again at MAD several years later in the exhibition Collaboration: Artist and Architect, which highlighted the rapidly developing role of stained glass in post-war art and architecture. Opening in 1962,, the display contained a commissioned window by Sowers for Temple Mishkan Tefilah in Newton, Massachusetts (pictured). An expansive screen, the wavering leaded lines hold together geometric panes of glass. Dark blues, reds and browns and yellows punctuate the primarily colorless glass. Stained glass and other work for secular spaces were included in the exhibition as well to demonstrate the “rejoining [of] the arts under a common roof,” according to the exhibition catalog. The exhibition encouraged audiences to see stained glass as not only ornamental, like the work of Louis Comfort Tiffany, but also as an art form equal to that of architecture. The Museum demonstrated its support for Sowers’ scholarly and practical work in stained glass by acquiring a panel from a dedicated exhibition of his work in 1975, titled Jive Light (pictured).

“New Stained Glass” in the 1970s and Beyond

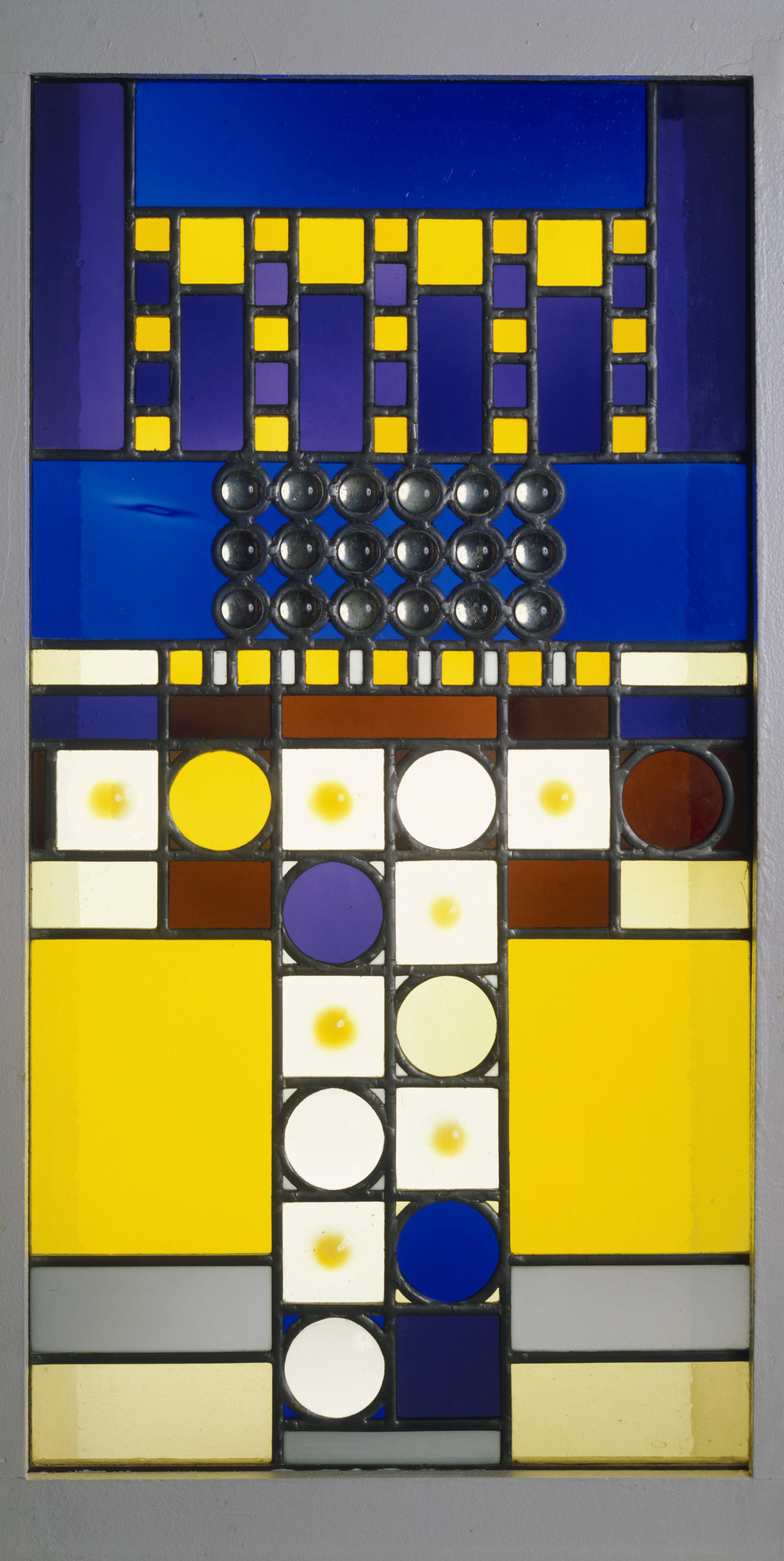

Having affirmed stained glass’s new-found relevance for contemporary architecture, the Museum further expanded the craft’s influence in the 1978 exhibition, The New Stained Glass. On view were individual, “autonomous glass art” objects created by ten male artists from across the U.S. and Europe, all of whom were celebrated as both designers and fabricators. Colliding with the proliferation and popularization of Pop Art, these artists produced expressive pictorial and abstract works exploring a variety of subject matter and made with nontraditional materials, such as photo transparencies and x-rays. Other works featured satirical subject matters, such as Richard Posner’s The Big Enchilada, depicting the White House during the period of the Watergate affair. Also included was the work of Paul Marioni, a self-taught glass artist who had only started working with the material several years prior. Marioni’s oversized composition featured a portrait of the Surrealist artist Salvador Dali, with integrated lenses and mirrors to bring the portrait to life. The Sink (pictured), now in MAD’s permanent collection, was also included and is part of Marioni’s first body of works in glass that had debuted in a San Francisco gallery only a few years prior. The catalog (pictured), praised the technical innovations in stained glass that had made possible a “means of expressing visual relationships and personal attitudes that often have not previously been relevant to the medium.” For MAD, this “new stained glass” was not dependent on architecture or religion, but was art in its own right.

Even as stained glass continued to develop as a means of personal expression, artists maintained a connection to the broader ecclesiastical history and significance of the medium. Madonna and Prada: A Day in the Life of Madonna (2012), by Joseph Cavalieri and part of MAD’s collection,takes the form of a triptych, a three-part, folding, portable form that has traditionally been used in the Catholic Church for devotional purposes (pictured). Using enamel paints on glass, and often installing a lightbox to backlight his works, Cavalieri upends the traditional iconic presentation of Madonna and the Christ child. Socialite Paris Hilton takes the place of the Madonna in the central panel and cradles a Prada high-heeled shoe in her lap. The side panels illustrates a debauched night out, with an angelic DJ spinning for an inebriated crowd of revelers. These scenes take place in Gothic architectural settings that recall traditional church spaces. Main figures of the composition retain halos, a common practice in medieval Christian art, and nuns appear with Prada accessories as well. Flipping the religious associations with stained glass on its head, Cavalieri mines sacred iconography to comment, critique, and satirize contemporary consumer culture and its pop icons.

MAD’s most recent exhibition dedicated to stained glass, Brian Clarke: The Art of Light, proves once more that that innovations in stained glass are inherent to the medium. Clarke is a preeminent figure in contemporary stained glass who embraces and moves easily between the religious, architectural, and autonomous natures of the medium. Empowered by twenty-first-century technological advances, Clarke has produced work from an intimate to a monumental scale that demonstrate the almost limitless capabilities of stained glass to evoke wonder and captivate the eye. While we may not yet know what lies beyond Clarke’s achievements, we can be sure that MAD will be on the forefront of championing the illuminating and reflective qualities, both practical and theoretical, of stained glass.

—Alida Jekabson, curatorial assistant

Subscribe

Join our mailing list.

Join

Become a member and enjoy free admission.

Visit

Find out what's on view.