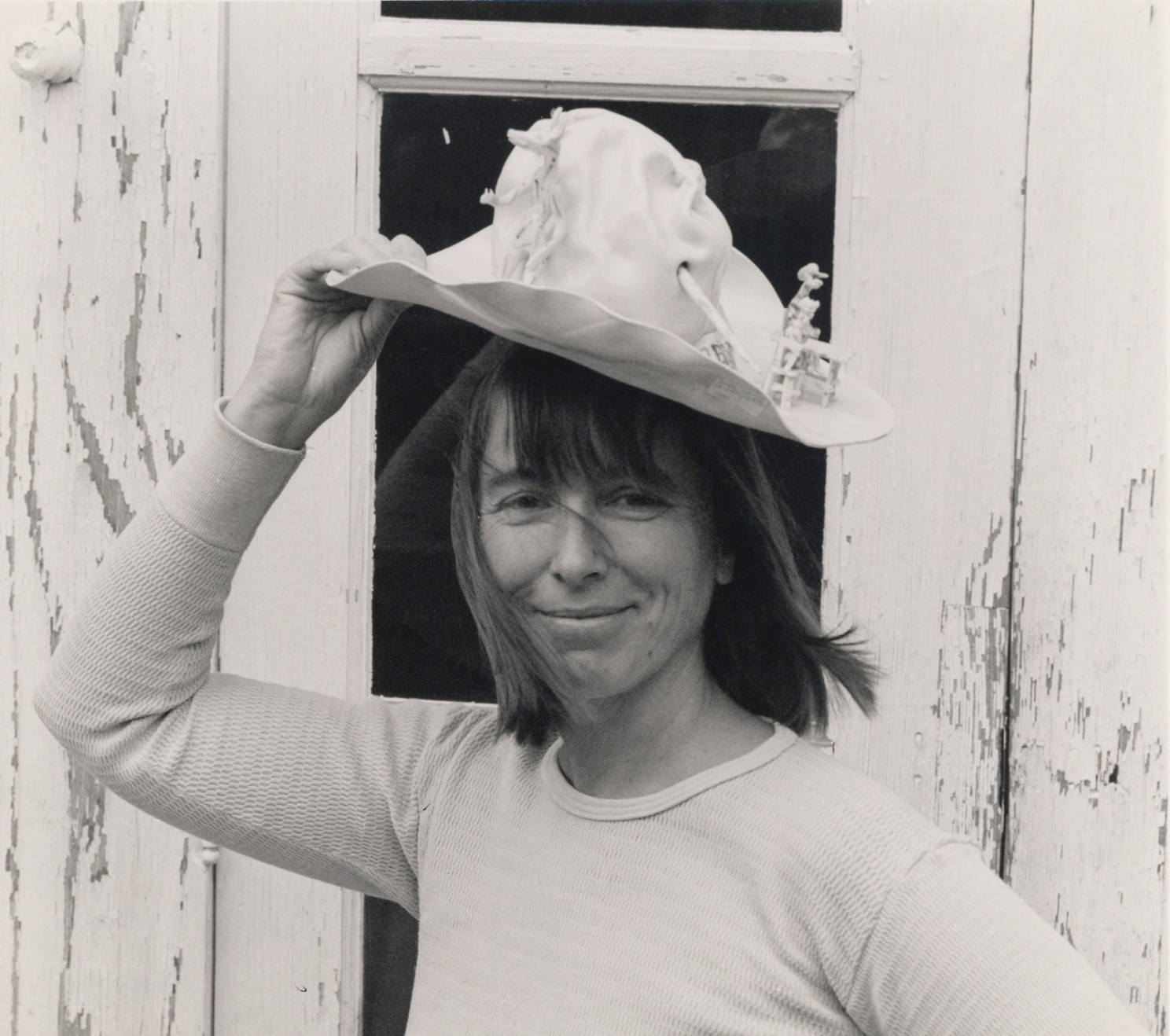

Interview: Coille Hooven

In 1962 you submitted a piece to MAD’s (then the Museum of Contemporary Craft) Young Americans exhibition which was accepted and displayed; now you’ve had a retrospective at MAD with more than 50 pieces. How do you feel about this experience working with MAD?

The whole experience has been amazing. My two MAD exhibitions have served as bookends for my half-century artistic career. I had spent the past eight years placing my work in collections, and because of my 1962 award, MAD was one of the first museums I approached with a donation. All these years later, MAD now has a young, female curator, [William and Mildred Lasdon Chief Curator] Shannon R. Stratton. I love how well she understands my work.

Can you speak about balancing a commercial practice and artist practice simultaneously?

After college, I was making pottery for studio sales and teaching. In 1979, my first ornament account was with The Metropolitan Museum, and thus began a new venture of Hooven & Hooven Porcelain. For over 15 years, I produced a line of porcelain ornaments that sold nationally. In 1996, my daughter took over the company, and that, along with my pottery production, allowed me to work full-time as an artist. In 1979, I had a residency at Kohler where I had no wheel, and this began a new approach. I redefined my form in porcelain as more sculptural, with a deeper feminist following.

What and who has inspired and influenced your artistic practice?

My parents were major influences. They were both highly creative individuals: My dad was an architect, and my mother was a teacher and a poet. We had heady summers during the 1960s in Provincetown with the abstract expressionist artists there, before they were so famous. I met Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Barnett Newman, Jack Tworkov, Hans Hofmann, Willem de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg. Henry Geldzahler was there as a grad student, and when he told us that he would be a curator at the Met, we laughed. Ivan Karp was there, before he had a gallery. They were real artists living edgy lives; we were a family rich with a creative life.

[Ceramist] David Shaner was my mentor in so many ways. He truly inspired my own journey with clay. His work ethic, his ability to find meaning, and his complete authenticity resonated with me. I soaked up his aesthetic and his advice. This was such a gift for me.

In 1970, I spent a week living with Peter Voulkos and Ann Stockton in Berkeley. I had met Peter in 1958 through David, and afterward I went back to Baltimore and quit my teaching job at MICA, left my husband, and came to the Bay area. I encountered the exploration of feminism, and I was able to find myself through my art. I had no idea what I would do once I landed in Berkeley. It began a new journey as a career artist.

You chose to work in porcelain in a small scale at a time when stoneware and earthenware at a much larger scale, sometimes massive, was the norm. Why did you choose porcelain specifically?

I have been working with clay since college. When I discovered porcelain my life changed forever. I loved the delicacy and intimacy of porcelain. Porcelain is one of the most difficult clays to work with—it’s clean, it’s white, it has its own truth. Porcelain is a tempestuous partner: get it too wet and it will collapse, get it too thick and it will crack. Temperamental, it is affected by weather, the barometer and its own degree of malleability or plasticity. Even in a well-sealed plastic bag, porcelain stiffens up over time. This clay has a willful mind of its own. It took me years to become its partner, to hear its tune. I learned to say, “What are we ready for today?”

Can you talk about the importance of fantasy and storytelling in your work?

I can put context into a piece, I can tell a story, and the viewer hopefully feels that and understands it. My work is about movements, specifically the way the clay captures this sense of movement and gesture. The shapes seem to move. The teapots to me have a feeling of movement, and the shoes aren’t shoes but they are boats in motion. Then there is the narrative the viewer creates; the work is available because of its representational nature. Here is this woman, with snake hands, transforming with a cloth over her head. She is not allowed to feel the trap she is caught in—she has to work her way out of this. In Rosebud, we have despair; we have budding sexuality, the pressure of having a career, the falling-in of adulthood, the pressure of sexual performance. I sometimes feel so sad and angry for the limited role that women have been assigned historically in our societal development. I want to hold that history so that younger women can know their roots.

Most of the works in Tell it By Heart are from the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s. How would you describe the evolution in your work and are you still working today?

The scale of my work is delicate—private, small, inviting. It doesn’t hit you over the head. You have to bend down and look at it—it’s about intimacy. Some works are tender, playful, and surreal, and others hold a vulnerable narrative about women’s issues. I use common handmade household items to reference and ground the viewer—like shirts, shoes, pillows, pies. The story or interplay is often about family and relationships. During my coming‐of‐age, calling myself a feminist was important. It is a word that reminds me of my past and holds me accountable in the present. I would catalogue the chapters of my oeuvre as Maiden, Mother, Wife, and Crone.

Is there something you wish the visitors take away with them when they see your work?

I want to welcome viewers—this is an opportunity for them to engage with their own stories. I go deep when making a piece, and I want to invite people in. My earliest works captured for me the dearness of life, the tenderness and joy of being alive. As I aged, I consciously brought in the darker side and grew to incorporate specific issues and feelings. These are my interpretations and narratives, but they also contain the narratives each viewer creates. The recognizable objects in the pieces provide an easy entrance for viewers, but once inside, they are on their own to interpret.

Subscribe

Join our mailing list.

Join

Become a member and enjoy free admission.

Visit

Find out what's on view.