Fabric of Change: The Quilt Art of Ruth Clement Bond

This article was originally published to commemorate Black History Month on February 22, 2017, at the start of our current political administration. Unsurprisingly, most pieces by Black artists in MAD's collection serve as forms of protest, a reminder that craft has been and continues to be a powerful tool of protest in the United States, especially for marginalized groups such as People of Color, LGBTQ+, and women. It also points to the uphill battle the Black community has faced to be treated as full citizens long after the Civil Rights Movement that took place forty years ago. Despite being an integral part of the fabric of American society and history, Black communities continue to suffer the effects of systematic racism that infiltrates our country. They have had no choice but to continue the fight for their livelihoods, freedom, and survival.

In the midst of a devastatingly precarious period in our country’s history, as we suffer the loss of over 100,000 people from the Covid-19 pandemic, Black people—most recently George Floyd, Ahmad Aubrey, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade— continue to die as a result of police brutality and hate crimes. Protests can take many shapes and forms, and this article focuses on an early example of protest art from the 1930s, the “TVA (Tennessee Valley Authority) quilts” of Ruth Clement Bond. Bond was a pioneer who sought to highlight the importance of Black people to the labor force and represent the progress of the era’s public infrastructure projects through quilts and community-building. One of these quilts included the now iconic Black Power Fist, which remains ever associated with revolution and solidarity. We have reached a crucial moment in the US history of protest and activism. Today's fight is yesterday's and we hope that history stops repeating itself. Change requires solidarity, support, persistence, community, and political will. Black Lives Matter, today and every day.

—Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy, assistant curator

As recently underscored by the Pussyhat Project, craft—and especially fiber—has long been used as a tool of political activism and community unification. Such is the case with the 1930s TVA quilts designed by Ruth Clement Bond, of which MAD has three appliqué panel versions, made by Rosa Marie Thomas, in its permanent collection. In her only venture into quilt design, Ruth Clement Bond (1904–2005), and the African American women who executed the panels, broke ground for art entwined with political messaging crafted in the home. Through this project, Clement Bond, an educator and advocate for social change, redefined the practical uses and artistic limitations of quilting.

Despite being born to an affluent African American family from Kentucky and having a Master’s degree in English from Northwestern University, Clement Bond spent the years 1934–1938 in a segregated housing community with rudimentary amenities in Alabama. She moved there with her husband, J. Max Bond, PhD, who was working for the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) as director of the Black workers in the construction of the Wheeler Dam—a New Deal initiative established the prior year. During this time, Clement Bond designed a series of quilts for a “home beautification” project for the wives of the Black TVA workers, including Rosa Marie Thomas. The title of the series, “The TVA Quilts,” reflects not only the context of the pieces but also their subject.

Clement Bond’s designs were foremost a celebration of the expanded opportunities for African Americans under the New Deal. She undertook the quilts as part of a larger project to inspire other Black women to self-reliantly make homes through craft. Although she did not know how to quilt, she drew shapes on brown paper and then selected colors and fabrics. These were sewn into quilts or panels by communities of Black women to create compositions reminiscent of the work of Harlem Renaissance painter Aaron Douglas.

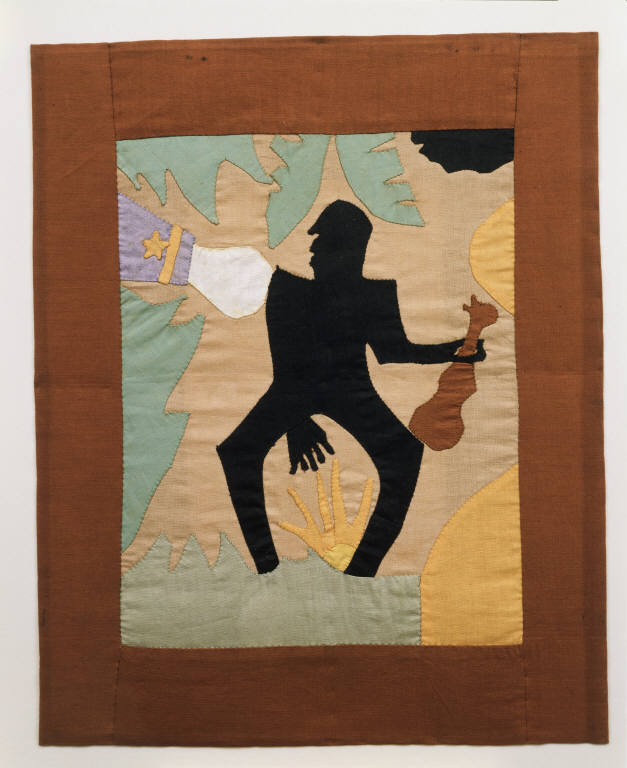

One panel directly depicts the work of Black men at the TVA through the Black silhouette of a man directing a crane, surrounded by brown forms representing the dam. Another, colloquially known as the “Lazy Man quilt,” shows a Black man holding a guitar, choosing between a life of pleasure, represented by the abstraction of a woman on his left, and a TVA job, symbolized by a uniformed arm tugging at his right shoulder. According to Clement Bond, “He chose the TVA job. It has a hopeful message. Things were getting better, and the Black worker had a part in it.”

The most critical piece in the series is the “Black Power” quilt, in which a Black fist breaks through the ground holding a red lightning bolt; a shining sun and an American flag occupy the panel’s upper corners. It was meant to signify the electric power that these men were providing to the area. However, the quilt was interpreted by young Black men interning for Bond as a symbol of the power of African Americans as a unified group. Today, the raised fist of solidarity is most widely recognized for its use as a symbol by the Black Panther party in the 1960s. Clement Bond stated that many believe the term “Black Power” to have originated with the TVA quilts. This panel, in particular, became an emblem of the effort to improve the quality of life of African Americans by African Americans 30 years before the Civil Rights Movement. For Clement Bond, the quilt was evidence that “we were pushing up through the obstacles—through objections. We were coming up out of the Depression, and we were going to live a better life through our efforts. The opposition wasn’t going to stop us.”

In subtle ways, Ruth Clement Bond and the TVA's Black women conveyed messages about the importance of Black labor and their authority over their own lives. Clement Bond continued her work as an educator, diplomat, and advocate for women, becoming a founder of the African American Women’s Association and an active member of the Foreign Service Women’s Association, among many other organizations. The story of the TVA quilts honors the African American men who labored on this project, their wives who stitched their reality into these panels, and the legacy of Black craft, which has transformed the very fabric of American history.

—Angelik Vizcarrondo-Laboy, assistant curator

Subscribe

Join our mailing list.

Join

Become a member and enjoy free admission.

Visit

Find out what's on view.