Born in Houston, Texas, and based in Brooklyn, Charisse Pearlina Weston is a conceptual artist and writer whose practice is grounded in profound material and symbolic investigations of the intimacies and interiors of Black life. In her practice, formal explorations of glass, poetic texts, abstraction, sound, video, and photography are used to articulate the artist’s concerns with the complexities and consequences of violence, which she views as an intimate act of power and subjugation. Her glass installations and sculpture not only confront the everyday risk of anti-Black violence, but also gesture toward resistance and survival.

Now on view in the Museum’s lobby, this sculpture is part of an ongoing body of work in which Weston explores the uses of glass in contemporary architecture and surveillance technology as signifiers of intimacy, freedom, and power. Considering how this seemingly neutral material has affected Black intimacies, interiors, and spatial movement, the enfoldment and layering of the glass are meant to suggest withholding and concealment. In this inner “fugitive” realm, Weston posits, there is space for Blackness beyond the reach of harm.

Weston is MAD’s 2021 Burke Prize winner. She is also an artist in residence in the Museum’s 6th floor Artist Studios.

Image: Untitled (lean/wire fuses), 2021 Glass and etching

Juror Statements

Andrew Gardner

Folding, bending, layering, and cracking—artist and writer Charisse Pearlina Weston pushes her chosen media to the limit, whether working in glass, language, photography, or a combination of those and more. Her sculptures incorporate mass-manufactured sheet glass—from discarded picture frames, for instance—in a variety of surprising ways, pointing to the transmutability of a material that lies at the heart of our modern way of life. Materially, glass is an ever-present mediator, negotiating in the form of screens between the physical world and the digital; in the form of windows between the outside and the in; and in the form of lenses between the photographer and her subject. Glass is chiefly valued for its transparency, a material that lets us see through, into, and beyond. In this pandemic age, glass and its petrochemical relative, plexi, both protect and partition us from experience: our interactions with others increasingly take place through glass, from digital touchscreens to transparent barriers at the grocery checkout. Glass is also reflexive, a medium through which to see the self. Whether experienced on our phones or in the mirror, glass can remind us of what we look like and who we are, and perhaps also point out the things we wish weren’t true.

Weston’s dexterity with glass, language, and the photographic image comes in part from her training as an artist, curator, and writer, whose interest, she writes in her artist statement for the Burke Prize, centers on the “everyday risk of anti-black violence and the precocity and malleability of blackness in the face of this violence.” Importantly, the Brooklyn-based artist’s practice also draws on her own life experience, including formative years in the predominantly Black working-class neighborhood of Hiram Clarke, in Houston. Her work, as she writes, reveals the “fragility and fungibility of Blackness” through “reusing, deconstructing, and reconfiguring materials.” Glass, a medium of primary concern to an institution rooted in “traditional” craft media, is a formal and theoretical foundation for Weston’s sculptural practice. But it is glass transformed—into broken shards and folded sheets and layered compositions—that speaks to the medium’s contemporary resonance. Glass is the very basis by which we experience and see the self, and regard those around us, and by which those around us regard us, in turn.

If there is one word to describe Weston’s work, it might be “precarity.” One sculpture, for example, physically teeters on the edge of a concrete cinderblock. The interplay in her work between text, image, and material requires delicate attention, and the work itself is fragile; it challenges the risk of its own fragility, or has succumbed to that fragility, perhaps pointing to the existential precarity of living while Black in America. Weston knows of this persecution, and yet her work chooses to regard brilliance in equal measure, to surface the gleaming genius of being Black in a white man’s world—and thriving, despite centuries of persecution, bondage, and disenfranchisement. The folded edges of her bent glass works seem to remark on this persecution and brilliance simultaneously, serving as physical manifestations of a metaphorical precarity.

Charisse Weston is a worthy recipient of MAD’s 2021 Burke Prize. In her artist’s statement, Weston describes her artistic practice as one “whose sole purpose is to raise and extend points of social inquiry in the service of Black people.”[3] It is deeply serious and powerful work, and it’s beautiful, too. It’s work that challenges the status quo, and offers a new way of looking at and thinking about craft. An artist who deftly navigates the complexity of the present moment and hints at future possibilities, Weston will undoubtedly help to steer the conversation about what craft is and what it can be now and into the future.

Andrew Gardner

Curatorial Assistant, Department of Architecture & Design, The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Gabriel de Guzman

In her work, Charisse Weston expresses the material qualities of glass, focusing on its poetic and conceptual significations to correlate with the complexities of the Black experience in America. Glass is deceptive in its appearance of transparency. Because of its reflective quality, it distorts both the image seen through it and the one shining back. Often incorporating photographic imagery into her work, Weston reminds us that photography and glass have been interconnected historically. As a lens-based medium, photography relies on the properties of glass, which allows light to pass through it to create an image on a photosensitive surface. Glass plate negatives were used in the nineteenth century to capture light impressions, and lantern slides were used for projecting photos. In a 1978 exhibition of contemporary American photography at the Museum of Modern Art, curator John Szarkowski proposed a dichotomy in which a photograph can be either “a mirror, reflecting a portrait of the artist who made it, or a window, through which one might better know the world.” Ultimately, it is both at once.

Glass as a medium also functions simultaneously as mirror and window, letting us see ourselves and look into another world. In architecture, the material allows a view into a desirable place, storefront window, luxury space, or breathtaking landscape. However, glass is also a barrier that denies access at the same time as it entices the viewer to notice what is just beyond reach. Windows separate interior from exterior, us from them, mine from yours, and they are often blocked when temptation seems too risky and desired profits must be secured. During Black Lives Matter protests in summer 2020, retail shops boarded up their glass storefronts to prevent looting. Valuable consumer goods could be protected, but invaluable Black lives could not. The use of glass for the surveillance and policing of Black people through broken windows theory and other tactics serves as an excuse for racist behavior. Misguided concepts about disorder and crime prevention are used as justifications for punishing Black and minority groups without offering the real support necessary to advance communities of color. Broken glass policing is also a cover for gentrification. As the process accelerates, new glass buildings go up, and bigger windows allow for greater light, reflection, and airiness, showing that the neighborhood is safer, but for whom?

Weston creates folds and fractures in glass to evoke the contradictions inherent in the medium, exploiting the distortion that is inevitable when engaging with glass. As Weston describes glass is “rigid but malleable, delicate yet dangerous, transparent but also distorting, fracturing, and therefore, opaque.” Poetic texts in Weston’s works also present fragmented narratives that suggest historical trauma, bringing the viewer in while keeping them at a distance. Are these works of self-expression, or are they external explorations? The artist grapples with the complexities revealed by this endless questioning. Weston’s work exposes the fragility, vulnerability, and perceived expendability of Blackness in a society that associates social unrest with impoverished minority groups, yet her sculptures and installations assert themselves in the space. Arranged as they are on the floor, they require us to walk around them, approach them, get close to them, and stand back from them. We gaze through the glass and see ourselves on its surface. If we look closely, and carefully, this body of work shows us who we are and where we need to go.

Gabriel de Guzman

Director of Arts & Chief Curator, Wave Hill

Indira Allegra

Charisse Pearlina you had said:

the romanticization of craft. I would say that it is no longer the sole responsibility of craft to build bridges between people who struggle to value each other. It is no longer necessary to use wood and fiber to craft a swinging span between the shallow and the spiritual, the analog and the digital, that which is handmade in a studio and that which is handmade in a factory, something called fine art and everything else. These arguments are binaries that have kept many of us distracted from what our materials could teach us about being.

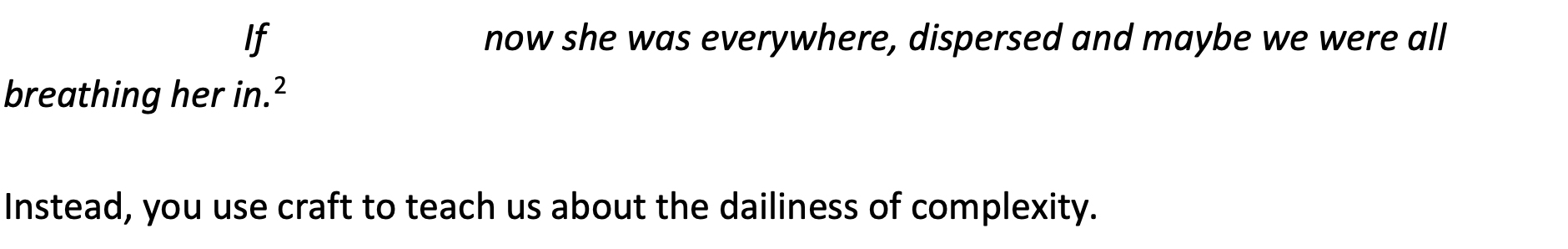

Instead, you use craft to teach us about the dailiness of complexity.

Just as Cannupa Hanska Luger lit my torch in 2019, I light your torch, Charisse, as the next winner of the Burke Prize. I am so grateful to welcome you to this growing lineage within contemporary craft. The investigation of tension in my work is allowed to break in yours. You give me permission to be honest about the ways in which I am shattered. You show me that I can be swept up and melted down and remade into other texts—and quietly.

“Quiet is the expressiveness of the inner life,” writes Kevin Quashie in The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture, “unable to be expressed fully but nonetheless articulate and informing of one’s humanity.” As a concept, quiet helps us to recognize the presence of Black subjectivity beyond a stereotypically stylized public expressiveness. It turns out that the recognition of interiority is radically humanizing within a dominant American culture that responds most quickly to visual volume. With a brave hand, Charisse, you lift a sheet of glass to say:

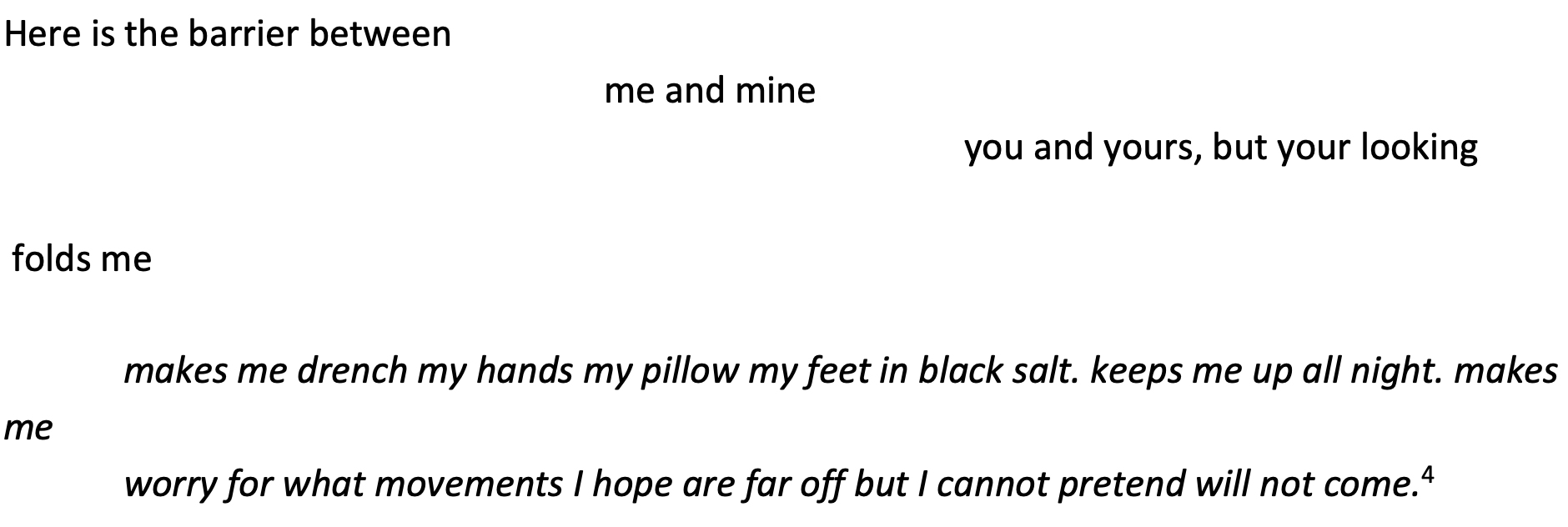

Charisse, do these “movements” that are outside of yourself think there is something fungible about your body? Do the specters I feel in your work author this performance you offer—drenching your feet in black salt? Yes, I believe craft is performative, but we cannot assume that who we perform for is human now, got to be recognized as human then, or even ever cared to be. If I lean in, I hear you offering a fragile poetic that points toward multiple futures where craft explicitly embraces multipolar engagement from all of these viewers—the human, the never was, and the never will be—looking at the same point through multiple planes of existence. These are the presences who make our present moment delicate, folding time in on itself into a black point perspective or blueprints for worry. After all, the dead have always outnumbered the living, and nonhuman life and matter far outnumber those who are human. Thank you for using Black cultural production as a methodology to show how those of us who are alive on the planet at this time have much to learn from both the ancestral human and ancestral material or force. Thank you for inviting your glass to articulate, melt, and rearticulate

Congratulations, Charisse. I hope you can see the face of your great-aunt Dolores grinning through your own as the legacy of the Burke Prize ushers you into its fold.

With great respect in the past, present, and future,

Indira

Indira Allegra

Artist & Burke Prize 2019 Winner

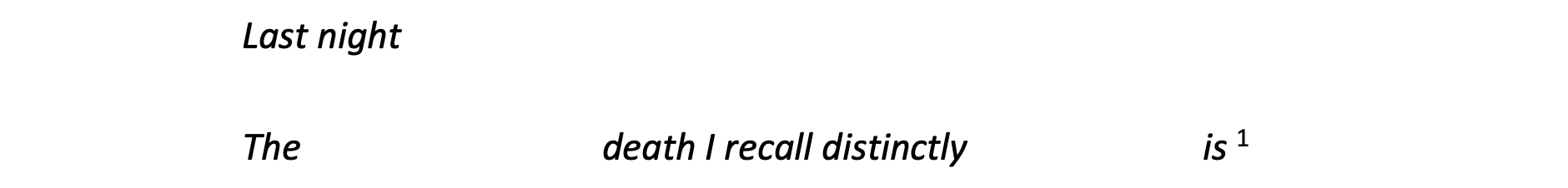

- Charisse Pearlina Weston. black point perspective or blueprints for worry. 2017.

- Ibid.

- Kevin Quashie. The Sovereignty of Quiet: Beyond Resistance in Black Culture. (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press), 2012, 24.

- Charisse Pearlina Weston. black point perspective or blueprints for worry. 2017.

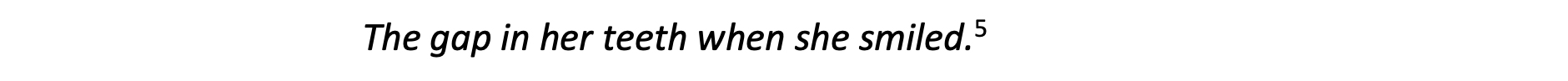

- Ibid.

Discover

Learn more about Charisse Pearlina Weston and the 2021 Burke Prize in our online exhibition.

Subscribe

Join our mailing list.

Join

Become a member and enjoy free admission.