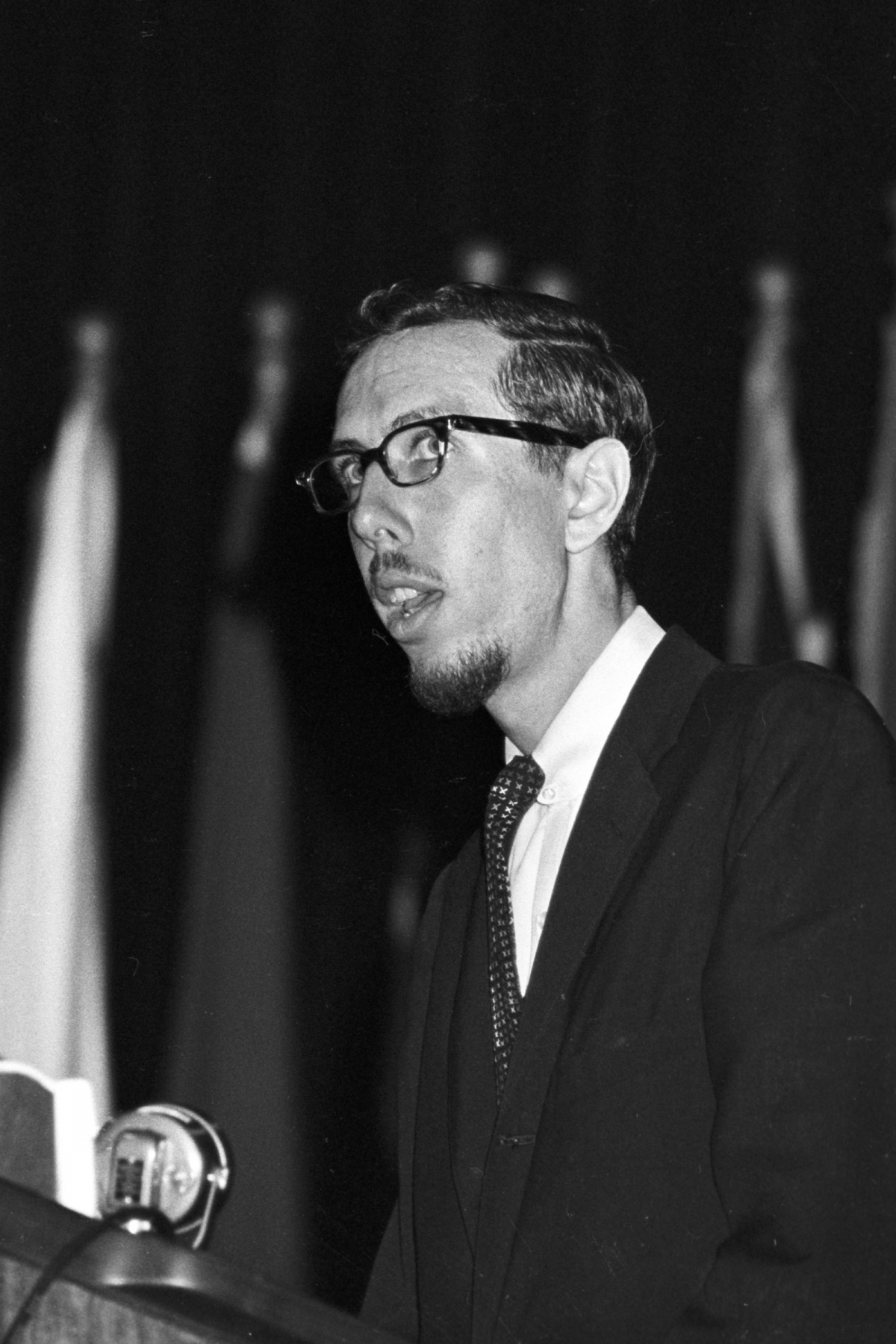

Remembering Paul J. Smith: Artist, Curator, MAD Museum Director

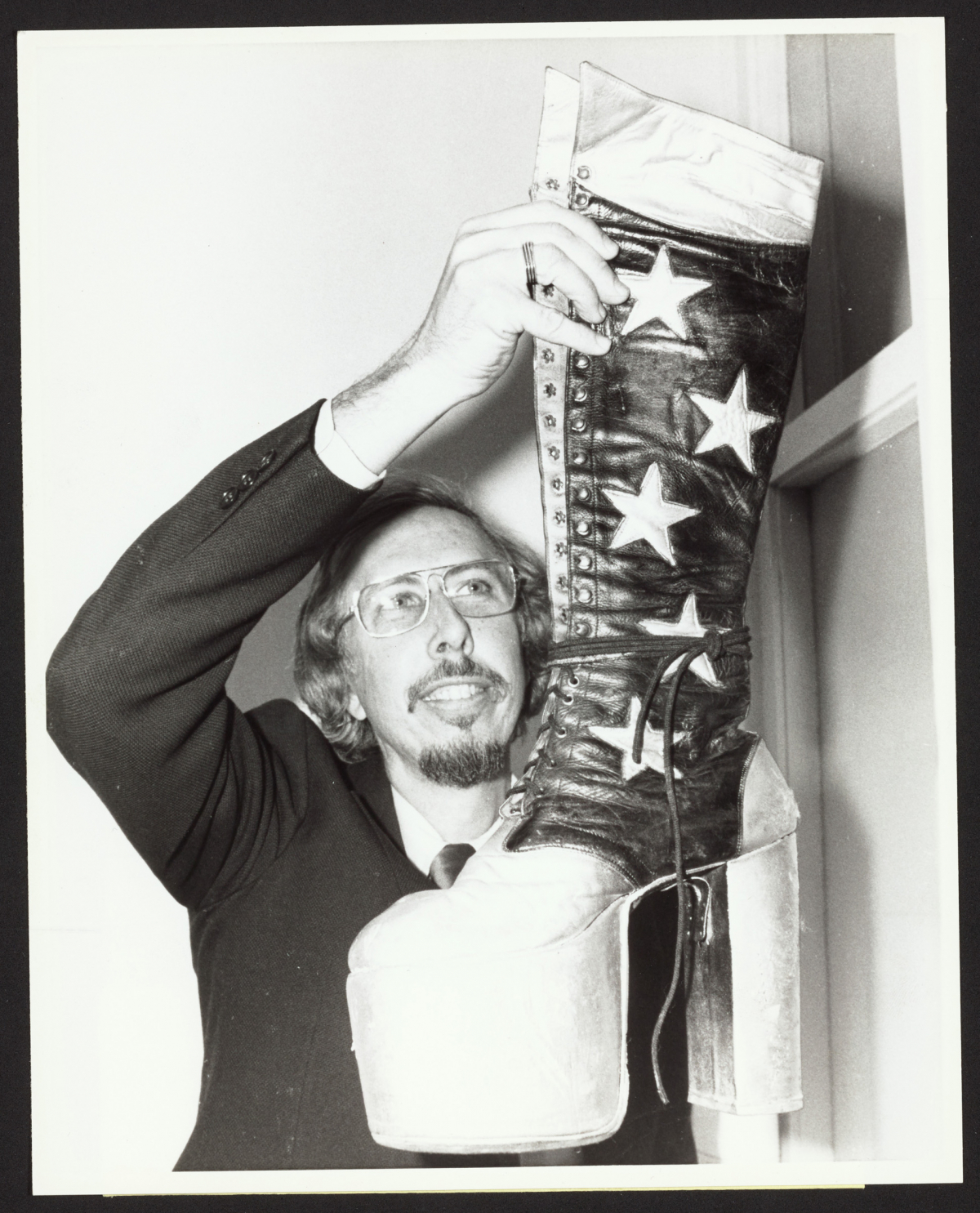

Paul J. Smith (1931-2020) served as the Museum's Director for over twenty years and forever changed the field of craft through his visionary thinking and pioneering approach to exhibitions and educational programming. Curator of Collections Samantha De Tillio remembers Smith's extraordinary career.

When remembering Paul J. Smith, it’s impossible to untwine his professional legacy from the history of the Museum of Arts and Design. Smith became involved in the institution during its earliest years and went on to be the Museum’s longest-tenured Director, setting the tone for the curatorial and educational programming for decades to come.

Smith’s association with the Museum of Arts and Design (then the Museum of Contemporary Crafts) began in 1956, when Director David Campbell invited him to participate in the Museum’s inaugural exhibition, Craftsmanship in a Changing World. At that time, Smith had also participated in the American Craft Council’s “Young Americans” competitions and exhibitions in 1954, 1956, and 1958.

When Smith joined the staff of the ACC in 1957, it was an established national organization in a period of growth and rapid professionalization; Smith was hired for a new position in which he created educational exhibitions and programs that investigated craft processes. These projects, which included Design Wood and Fiber Tools and Weaves (later repackaged as the 1960 exhibition Visual Communication in the Crafts [Fibers, Tools, and Weaves; Craftsmanship in Wood] for MAD), were sent to schools to engage students in art-based learning. During this time, Smith also became the assistant to Campbell, who served as Vice President and then President of the ACC. When Campbell became Director of MAD in 1960, Smith followed; he served first as Assistant to the Director (1960–62), then Assistant Director (1962–63), and finally Director of the Museum (1963–87).

A painter, ceramist, jewelry artist, and woodworker, Smith’s background as an artist informed the way he thought about his work at the Museum, including the exhibitions he curated and his ideas about the function of museums in public life. In an oral history for Bard Graduate Center, Smith recalled, "When I became director and was thinking, 'Well, what is the role of this museum?' I felt very comfortable about it being an institution focused on reporting on the new. ... [T]he main focus was being a showplace in New York for this emerging, outstanding innovative work from around the country, and some selected work from abroad."

Smith’s tenure as Director was clearly marked by experimentation, inquisitiveness, and community participation. When the Museum opened in 1956, it was the only institution in the country to focus on contemporary craft, and in the 1960s, when Smith took the helm, the nascent American studio craft movement was in one of its most exciting periods. The decade’s confluence of artistic creativity, social radicalism, and cultural participation provided a ripe atmosphere for Smith’s efforts to document the field through historical surveys, experimental projects, material investigations, and explorations into the relationship between art, craft, and design.

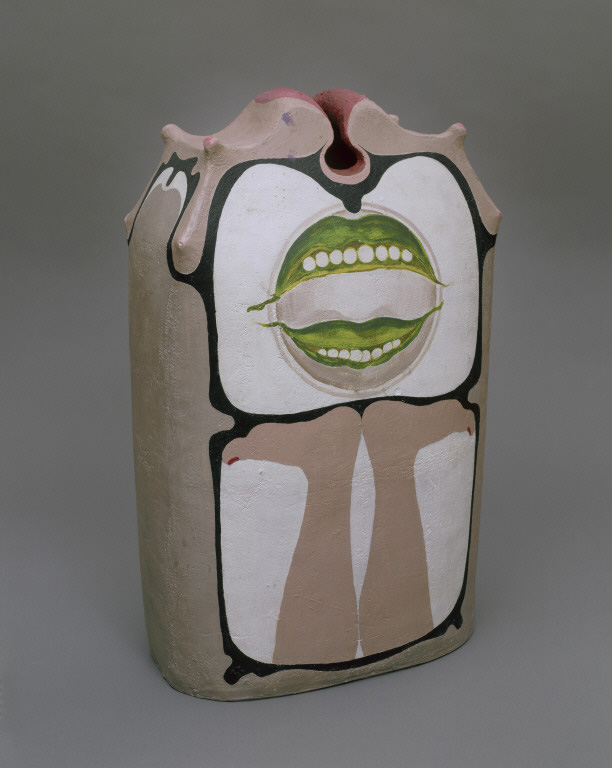

Numerous artists now central to the movement, including Peter Voulkos and Harvey Littleton, had their first museum shows at MAD; for many, the exhibitions also marked their first professional showing in New York City. In a cultural landscape devoid of craft galleries, the Museum provided a launchpad for artists to establish careers and realize projects—a function that MAD still fulfills through the Artist Studios program and the Burke Prize, among other initiatives.

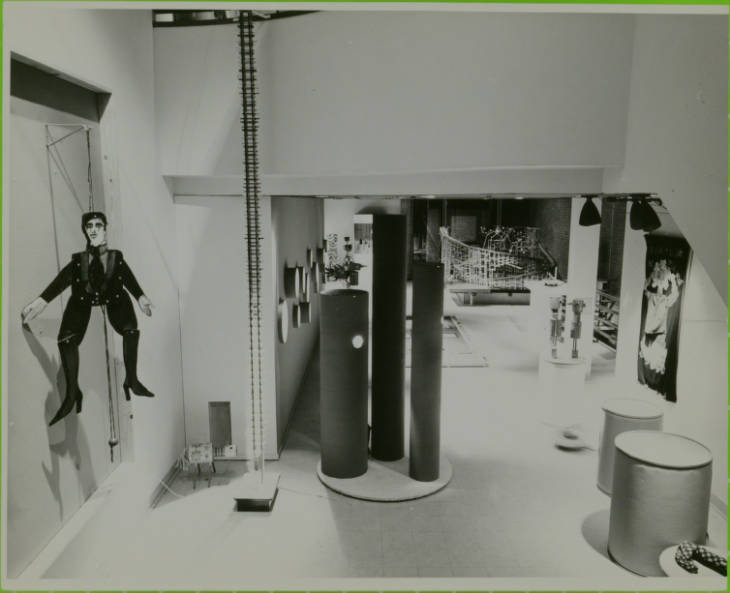

Smith described himself as "an artist who was creatively developing a program. The openness of exploring new ideas [central to the culture of the 1960s] had a dominant influence, and I know it had [a] direct effect on me and my thinking and on the museum and its program." In this spirit, some of Smith’s earliest curatorial projects sought to expand not just the scope of the craft field, but also the function of a museum. For example, Amusements Is … (1964) sought to break down the age-based barrier to play through artworks that motivated laughter, reflected amusing experiences, were self-activated or participatory, and communicated fun. Included was Charles and Ray Eames’ Musical Tower, a vertical xylophone played by dropping a marble down its bars, originally created for the World’s Fair.

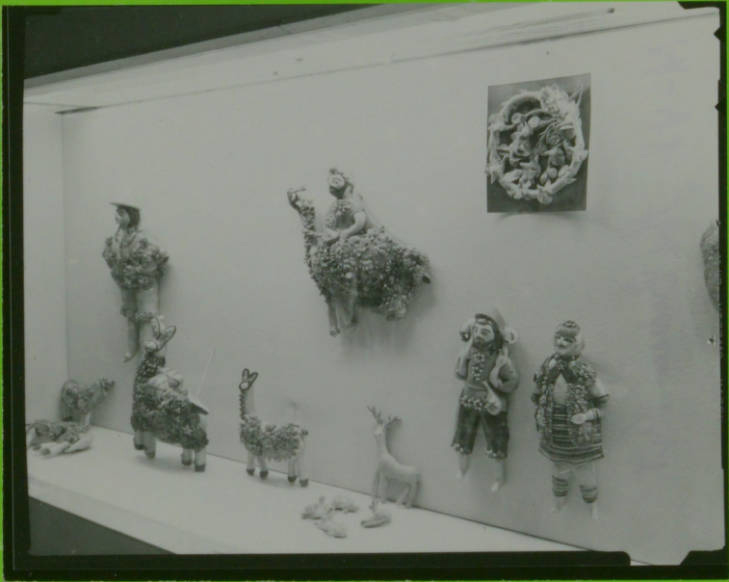

In 1965, Smith curated Cookies and Breads: The Baker’s Art, which highlighted the artistry in baking through elaborate breads sent from around the world, including Swiss Christmas bread, Cretan wedding bread, Jewish challah, and breads to honor the dead: Osso dei Morti (Bones of the Dead, made in Sicily for All Souls’ Day) and Fiesta de Muertos (Feast of the Dead) bread dolls from Ecuador, among others. The exhibition also explored the similarities between dough and clay, baking and kiln firing, and the creativity inherent to both.

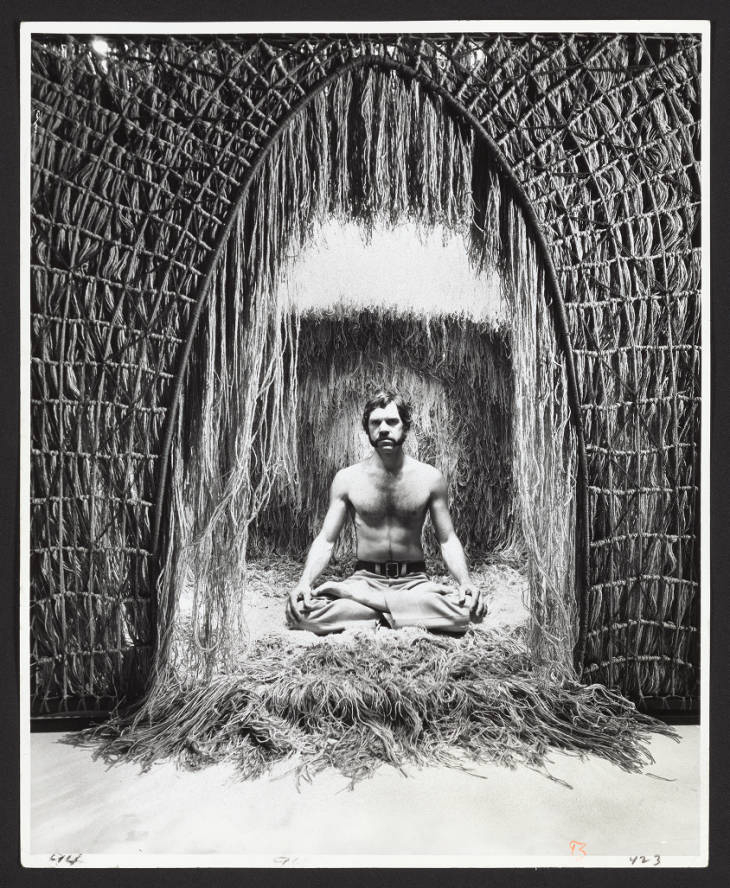

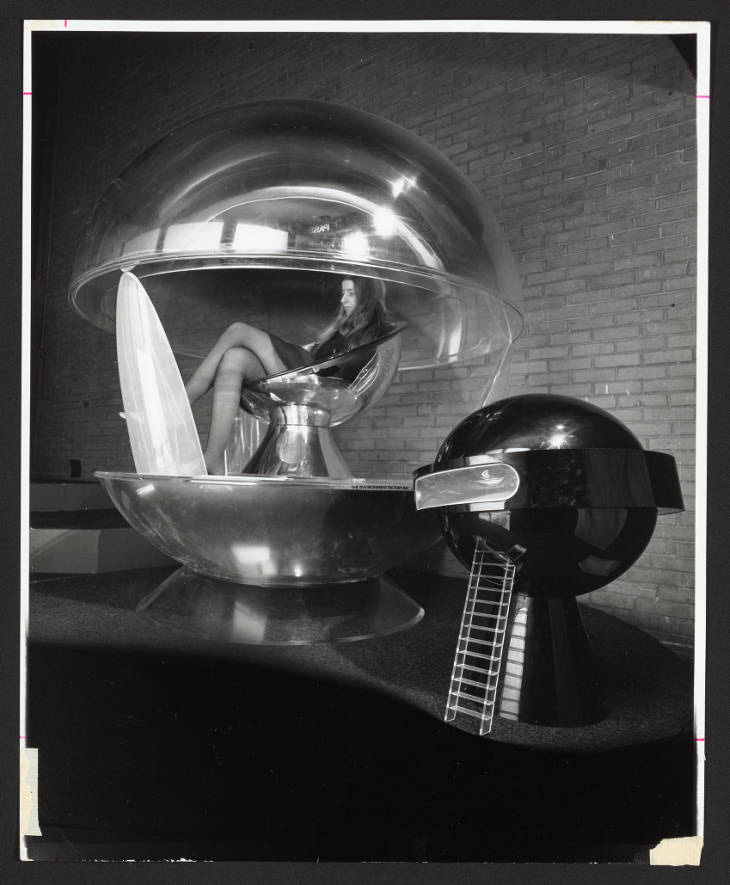

In 1970, Smith curated Contemplation Environments, which examined the way architecture and place making can create environments that nurture meditative activity, and drew comparisons between traditional houses of worship and countercultural philosophies.

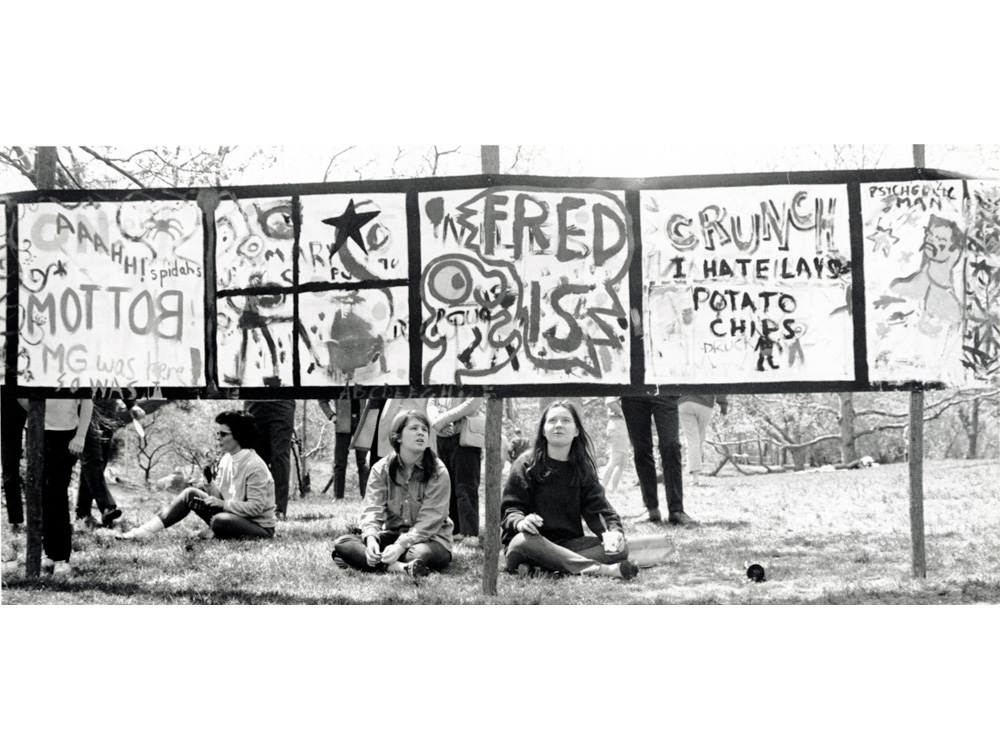

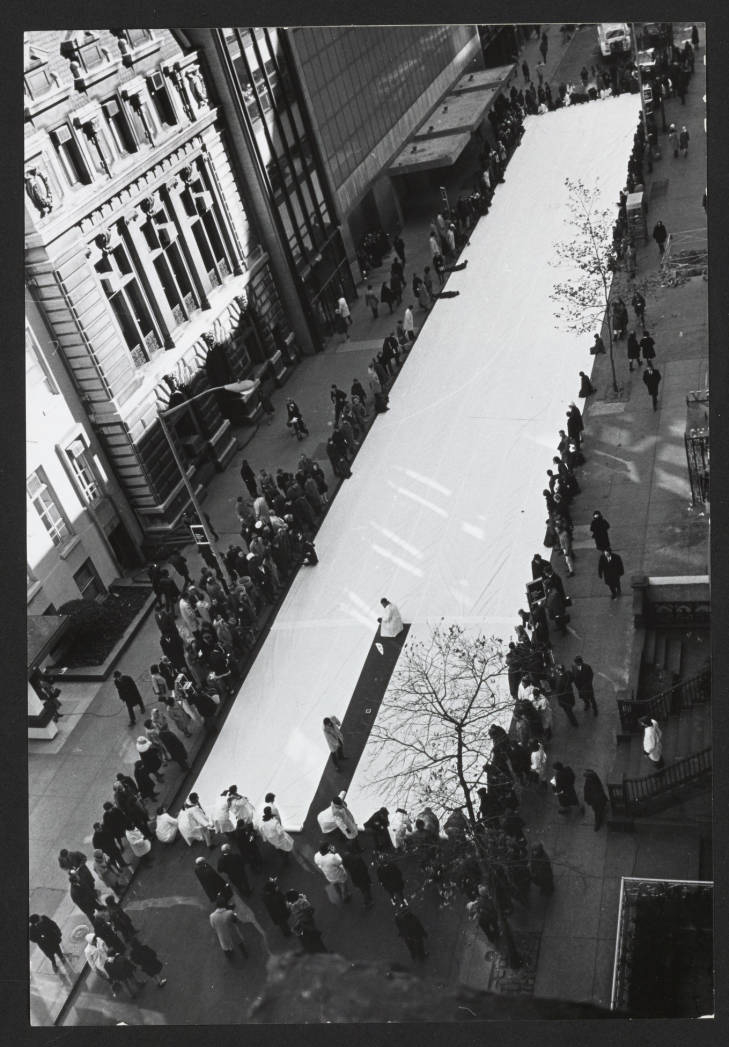

Smith’s tenure was also marked by participatory programs that engaged the Museum community both inside and outside of the galleries. When the city’s Parks Department designated a Craft Week in 1973, the Museum held a banner-making workshop called “Make a Banner, Fly a Banner,” followed by a parade around Rockefeller Center led by Marilyn Wood, a dancer with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. Concurrent with the exhibition Objects in the Open Air (1966), the Museum hosted a “Cartoon Performance” in Central Park and invited the public to paint together on a long-stretched canvas. In 1968, during the exhibition Made with Paper, which presented a comprehensive overview of paper and its range of applications, the Museum organized two performances. The first comprised the construction of a large piece of disposable paper on Fifty-Third Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, which would be washed away by the Sanitation Department (Smith had great success collaborating with New York City) to illustrate the possibility of new materials in combating littering; the second involved the launch of a weather balloon, elevated to high altitude on New Year’s Day and tethered by a gold-covered paper line.

Smith’s exhibitions and programs consistently broke barriers and embraced avant-garde perspectives in art. He disrupted the traditional “no touch” rule of museums through projects such as Feel It (1969), which transformed the Museum’s main floor into a maze of hanging plastic strips for the visitor to navigate, discovering objects through touch. In 1970, the Viennese collective Haus-Rucker-Co created an installation for the Museum, consisting of an inflated air mattress with large balls for visitors to jump on and play with. The project coincided with the annual meeting of the American Association of Museums (now the American Alliance of Museums), and at one point, during an open house that included the Museum of Modern Art and the American Folk Art Museum, MAD moved the installation into the closed-down street for the public’s enjoyment. Looking back on this era of experimentation, Smith commented, "A lot of this reflected the whole spirit of the sixties, of being open and trying new things. It was very much related to the happenings and the be-ins and people connections, and I think it didn’t seem out of place in the context of other things that were going on at the time." Simultaneous to these experimental projects, Smith curated exhibitions that would become historical touchstones for the field, most notably Objects: USA (1969) and CRAFT TODAY: Poetry of the Physical (1986).

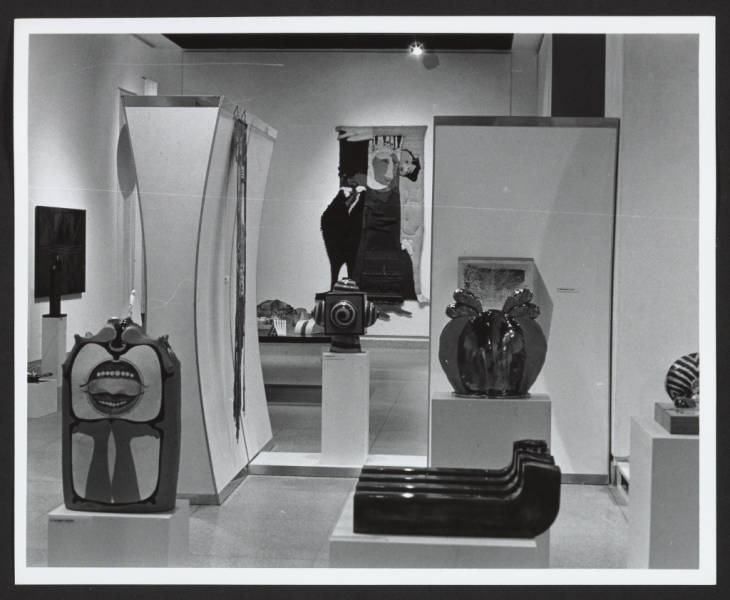

Arguably, the history of craft in the United States cannot be discussed without considering the legacy of Objects: USA, which was the first survey of the studio craft movement and tripled MAD’s nascent permanent collection. Smith was consulting curator for the exhibition—initiated by gallerist Lee Nordness and sponsored by the SC Johnson Company—which included over three hundred artworks from across the country, and traveled to twenty-two museums nationwide and eleven internationally. A variety of supplementary elements were produced in association with the exhibition, such as mail-order catalogs in which exhibiting artists could sell works. In 1970 ABC aired the associated documentary With These Hands: The Rebirth of the American Craftsman, featuring a number of the artists in the exhibition. Hundreds of thousands of people saw the exhibition globally, and it had an immeasurable and ongoing effect on the Museum, the artists, and the field. Looking back on the landmark exhibition, Smith said, "The idea was to put together a collection that would portray the vast range of outstanding work throughout the country. We decided early on to honor the established and important artists of the older generation and to include some of the most experimental new work by young emerging artists, if they were accomplished in what they were doing."

In 1986, to commemorate the thirtieth anniversary of the Museum, Smith curated the national survey exhibition CRAFT TODAY: Poetry of the Physical. The exhibition undertook to illustrate the many developments that had taken place in the field since Objects: USA seventeen years earlier, particularly the rapid professionalization and refinement that characterized the 1980s and would continue into the 1990s. It went on to travel to fifteen venues across the United States and abroad

The following year, Smith transitioned into the position of Director Emeritus, after twenty-four years as Director of the Museum and thirty years with the ACC. His contributions to both institutions cannot be overstated, and his contributions to the field continued until his passing. After leaving the Museum, Smith consulted with cultural organizations, advised collectors, and produced artist projects and commissions. He also advised the Toledo Museum of Art on the expansion of its glass collection and continued to curate exhibitions internationally, including Collectors’ Annual 1988: Contemporary Art Glass, Boca Raton Museum of Art; Studio Glass: Selections from the David Jacob Chodorkoff Collection (1991), Detroit Institute of Arts; and Celebrating American Craft (1997), Danish Museum of Decorative Art. In 2011, Smith curated the exhibition Objects for Use: Handmade by Design at the American Craft Museum.

Throughout his career Smith shaped the field through board and committee membership. He sat on the boards of Penland School of Craft and Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, the National Council of the Atlantic Center for the Arts, advisory committees for Boston University’s School of Artistry and Parsons School of Design, as well as the boards of the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation and the Lenore Tawney Foundation, just to name a few. He traveled to forty-six countries, including Botswana, Rwanda, Papua New Guinea, China, India, Germany, Morocco, Sweden, Australia, and Finland, to lecture, jury exhibitions, visit artist studios, and engage in diplomatic activities.

In 1987, Parsons School of Design awarded Smith an Honorary Doctorate in Fine Arts for his contributions to craft and design education. He was appointed to the American Craft Council College of Fellows in 1988. He received the Aileen Osborn Webb Award for Philanthropy, in recognition of his exceptional curatorial contributions to the field, in 2009, and the Legends Award from the Watershed Center for the Ceramic Arts in 2011. In 2019, just months before his death, Smith was honored with the Albert Nelson Marquis Lifetime Achievement Award at the American Craft Council annual conference, before an audience of artists, scholars, curators, writers, and arts administrators, who couldn’t have been there if not for the groundbreaking work done by Smith over his more than sixty-year career.

Smith’s legacy for the field of craft cannot be easily summed up—indeed, it will require decades of study to fully uncover. His endless enthusiasm, dedicated advocacy, and generous spirit are unmatched, and will continue to inspire generations to come.

Subscribe

Join our mailing list.

Join

Become a member and enjoy free admission.

Visit

Find out what's on view.